DESIGN SPOTLIGHT: MID-CENTURY ARCHITECTURE

21st March 2022A Brief History of Mid-Century Modern Architecture in Scotland

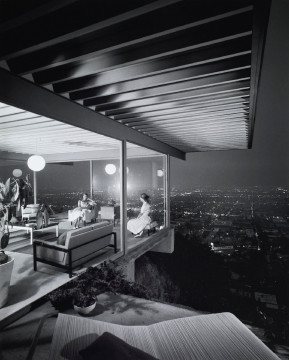

Here at Thomas Robinson Architects, both Tom Robinson and I have strong associations with mid-century architecture. In the 1960s, Tom’s parents commissioned architect Donald Downie to design their family home, which at the time was the ultimate showcase of modernism. We are now sensitively refurbishing and extending this house for the new owners, keeping its mid-century modernism at the fore. And I have warm and fond memories of playing at my aunt’s mid-century home in central Scotland, designed by my uncle, Geoffrey Keanie. I remember spinning around with my cousins on an Arne Jacobsen egg chair dizzily staring up at the teak ceiling panels, and sliding in socks on the expansive wooden floors, the room lit with sunshine from the huge windows – a rarity at the time.

What I found inspiring about this house was experiencing the spaces. There was a feeling of flow between areas, which were often divided by bookcases rather than walls. It was such a different experience to that felt in most other houses I’d been in and it deeply resonated with me. I loved being both in it and outside. The many views through the layers of building seemed to connect you to the landscape. It was a new and varied way of dealing with space. This house definitely played into my desire to become an architect.

Today, we are seeing more mid-century modernist houses in need of careful updating. Architects are also taking elements of successful modernist ideas and using them in their designs. Mid-century furniture remains in a consistent boom, too, with sideboards, chairs, tables, kitchenware and ornaments popping up in interior-design magazines and Insta pages.

To look at the successes – and some of the less good aspects – of this style of architecture and design I thought it would be interesting to take a look at its beginnings, with a potted history of how the style evolved, and why it’s influencing design today.

[Stirlingshire House, Practice principal Tom Robinson’s childhood home, designed by Donald Downie, now being refurbished by us. Find out more: Contemporary Extension Stirlingshire]

The beginnings of a new style

The early twentieth century could be described as conservative in architectural terms, but during the 40s and 50s, new building types began to emerge in Scotland such as collieries, airports and office buildings. They signalled the start of a distinct change in the way urban buildings were being expressed. The most significant building type to be developed in the mid-1950s was the tower block, which is possibly the most symbolic building type of the international modern movement

Before this, a forward-looking collection of modern architects set up an influential European group called CIAM (Congrès Internationaux d'Architecture Moderne), helping to spread the popularity of modernism among designers of the time. However, architects in a splinter group, Team 10, who had socio-architectural interests and included the English new brutalists, were critical of the modern movement, noting that it was mechanical and socially insensitive architecture. The emerging problems with the design and rollout of the tower blocks didn’t help the case for the modernist style and in fact CIAM disbanded in 1959.

[Tower Building at Queens College Dundee by Robert Matthew. Photo: University of Dundee.]

The Scottish influencers

A prolific mid-century modern Scottish architect of this period was Robert Matthew, who returned home to Edinburgh from London in 1953 having gained international acclaim. He became President of the Royal Institute of British Architects in 1962, promoting a whole philosophy of international modernism. Matthew added in a nod to the Scottish vernacular by using random rubble as cladding material on some of his buildings. He designed the now A-listed Edinburgh University 14-storey 40 George Square tower block (formerly David Hume Tower). The building’s lower ground floor is known as the Hub, and houses a café, shop and central atrium.

By the late 1950s, and with the fragmentation of CIAM, the popularity of tower blocks in Scotland was diminishing and there was a call for a more sensitive version of modernism. Now, the new solutions and architectural strategies for modern living weren’t being developed by the public architects building mass housing, but rather the architects who were designing private houses. Many of the leaders in this field were here in Scotland, such as Peter Womersley, Morris and Steadman and Jack Holmes. This became a prolific period of modernist house design, with many of the features returning to popularity today, including open-plan spaces, large windows and hard-wood floors.

Edinburgh architect Frank Tindall wrote in the weekly Scotsman in 1960 that modern house designs should ‘suit our less formal, more independent way of life…’ He said, ‘People stimulated by modern magazines want houses properly related to the sunshine with privacy and quiet and an aesthetic not derived from the past but from the modern materials themselves.’

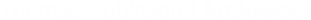

Scottish architects at the time became influenced by the architects of modernist American houses, including Louis Kahn, Pierre Keonig, Richard Neutra, Rudolph Schindler, Frank Lloyd Wright and Mies Van Dr Rohe and Sweden’s Alvar Aalto.

[The Stahl House (aka Case Study 22 House), Los Angeles by Pierre Koenig. Photos by [Julius Shulman/Getty Research Institute, © J. Paul Getty Trust]]

[The Kaufmann Desert House, Palm Springs, by Richard Neutra. Photos by [Julius Shulman/Getty Research Institute, © J. Paul Getty Trust]]

A new feeling of flow

Peter Womersley, one of the most influential Scottish modernist architects of the time, built Farnley Hey, pictured above, as a wedding present for his brother in 1954. High Sunderland, another of his designs, was built for the textile designer Bernat Klein. Both are great examples of the style at the time.

[Farnley Hey House by Peter Wormersley. Photos by Tim Crocker tim crocker / portfolio 1]

[Farnley Hey House by Peter Wormersley. Photos by Tim Crocker tim crocker / portfolio 1]

[High Sunderland House by Peter Womersley. Photos by Tom Parnell, CC BY-SA 4.0]

[High Sunderland House by Peter Womersley. Photos by Tom Parnell, CC BY-SA 4.0]

Although I’ve never visited these houses I feel a connection to them and the relaxed and flowing quality of spaces in their design. Plans are Miesian inspired and built around courtyards. The visual and sensual link to the landscape and nature from what looks like almost every room in the house is achieved by the subtle and sensitive organisation of the plan and massing and the use of expansive areas of glass. Interior spaces are divided by screens and fixed furniture which means each room flows into the next and long views through the house connecting you to the landscape are made possible.

I aim to apply a similar philosophy of flow to any design I undertake. The quality and flow of spaces that these mid-century architects were practising transcends their time and goes beyond modernism. It can be applied to any design. Even the most formal of houses need to flow and have multiples views set up within them – through the house and between the interior and outside. When successfully applied, the outcome is that you create houses which feel good to be in.

This is some of the feeling I had in my cousins’ house that I mentioned at the top of this blog. It had interconnecting flat roofs and was designed around a courtyard. Bookshelves divided spaces rather than walls, the fireplace was raised and those fabulous egg chairs were just some of the stylish gems in the interior design. The influence of Peter Womersley’s designs amongst the Scottish architects of the era was evident in this house by Geoffrey Keanie and very inspiring to experience first-hand.

[Central Scotland house designed by Geoffrey Keanie, Director Fiona Robinson’s uncle.]

The influence of America

Two other Scottish architects who were able to visit America on a scholarship in the mid-1950s and experience houses by Richard Neutra and Philip Johnson were Morris and Steadman. These two Scottish architects explored many ideas in their houses, including courtyard gardens, interconnecting flat roofs, painted brick walls, and open-plan living spaces with dramatic rubble chimney breasts. Their designs combined flowing spaces with cosy intimate areas. They also offered connection to the landscape through vast glazing and mono pitched roofs. Great examples of their work include the Principles House, Tomlinson House, Sillito House, Wilson House, Holden house and Homewood.

Tomlinson House was the first house designed by the pair, while they were final year students at Edinburgh College of Art. They wanted to bring in sunlight with a sheltered outdoor living area, and a feeling of connection between house and landscape. A stone core is at the heart of the plan, with the same stone used on the garden walls, screening the road. Two rectangles form the house, set at right angles. The strong horizontal flat roof is a recognisable feature of the time; however, these flat roofs were to cause problems in Scotland’s damp conditions.

The Wilson House sits on a ledge over a valley with great views. The elevation facing the road is windowless, with this side facing the view is heavily glazed. The architects created space by cantilevering the house and balcony out over the valley, much in the style of some of the Hollywood hills modernist houses.

[Sillito House in Edinburgh by Morris and Steedman, known as the Upside-Down House. Photo unknown.]

The Upside-Down House on sloping Blackford Hill was influenced by Japanese architecture (Morris and Steedman both visited Japan). The open-plan first-floor living space is designed to receive maximum sunshine, and enjoys a sweeping view over the city. The lower bedrooms are protected by the hill and a high garden wall. Materials used are white rendered blocks, with timber and glass for the upper level.

The Principle’s House is partly formed from ruins of 18th century outbuildings of the Adam-designed Airthrey Castle. The living areas face both Stirling Castle and The Wallace Monument, only seen once inside the building. The remainder of the house was divided into two wings and organised around a courtyard. Over the entrance and living area, the raised roof allows light to flood in and also creates the illusion of additional space.

Modernism becomes the norm

The ideas that were explored and developed in these impressive private houses soon extended into the realm of social housing where the trend moved from tower blocks to low rise, sensitively designed and human scaled housing clusters.

As these mid-century Scottish houses begin to age, us architects are being called to repair and alter them for 21st-century living. While they do present some problems in terms of low ceiling heights, and some materials with poor thermal properties, we must do our best to retain the significant style they bring to our built environment, and only refurbish and extend with great sympathy towards what the original architects set out to achieve.

[Stirlingshire House, Practice principal Tom Robinson’s childhood home, designed by Donald Downie, now being refurbished by us. Find out more: Contemporary Extension Stirlingshire]

References: Glendinning, MacInnes, MacKechnie, 1997 Miles Glendinning, Ranald Maclnnes and Aonghus MacKechnie, A History of Scottish Architecture. From the Renaissance to the Present Day. Edinburgh University Press, 1996.